Aurora Fernandez and Javier Mosas

via Caruso St. John architects

One of my favorite projects of Caruso St John is the Nottingham Contemporary.

AF: Why did you decide to study architecture?

PSJ: I just remember that when I was making the decision, I had no idea what an architect really was, and I think you only come to an understanding of that much later, well past the point at which you’ve been at college for a number of years. I’ve always been interested in making things and in our practice, I think that has manifested itself in the way in which we use models. I’ve always had a kind of manual dexterity, being able to make things in three dimensions very quickly, so perhaps there was an emotional empathy with the idea of applying one’s energy to build. My father was a very keen amateur carpenter, so I had an extensive training as a young boy in how to make furniture and how to use tools. I suppose there’s always been this intuitive interest in making, which I’ve enjoyed.

AC: My father is an architect, and the one thing that I knew when I was growing up, was that I didn’t want to be an architect, and my parents didn’t want me to be an architect. It was a hard profession and although my father’s practice was fairly successful, it was very tough to be an architect in Montreal. When I applied to university it was onto a pre-medical course, because everybody wanted me to be a doctor. But before I registered I decided I didn’t want to do that, and I did art history instead, a quick switch. I thought it was amazing to study art and the relationship of formal things to ideas, but even at an undergraduate level, I was dissatisfied. The new art history wasn’t really being taught, although I was aware of people like Rosalind Krauss, it was more of an old fashioned formal analysis. In the last year of my degree I transferred to architecture. When I finished architecture school there was no one I wanted to work for in Canada. Montreal was very depressed, because of the political situation, there was no work and no new practices had been set up for a decade. I wasn’t interested in going to the States, and I used to have family in England so I knew London, it didn’t seem such a faraway place. You could get a special visa because Canada was a part of the Commonwealth, and it was very busy in London.

AF: Can you remember what type of architecture you admired, or what type of work you had in mind, at the time you finished your studies?

PSJ: For a very long time I was the world’s biggest fan of James Stirling. I first came across his architecture in a book in my second year and found these images of the Leicester Engineering Building, that was the moment I really began to see what the potential of architecture could be, and I was amazed by the incredible three dimensional dexterity. It’s difficult to understand now, given that there’s so much architecture in the world, but at that time –late seventies, and I was looking at projects from the late fifties– the formal ambition of it seemed incredible, the exuberance of it. I suppose that for a long period of my studies, he was someone I worshipped. But later, as I was coming near the end of my studies, I became more interested in the Smithsons, the opposite, the English tradition, whom I was introduced to by my teachers at the AA, particularly Peter Salter, and to some extent by Peter Cook. I think by that time I was the kind of pupil who, if I agreed to do any work at all, tended to do the opposite of what my teachers wanted me to do. I was fascinated by the Smithsons. For me it was the beginning of a stepping away from an interest in architectural formalism toward perhaps an architecture that I could see had meaning in terms of how you lived and things that I was more familiar with in everyday life. But I did not manage to realize it in any of my student work, partly because I was in Peter Cook’s unit. He has vague memories of me being dissatisfied. I was a successful student but I was dissatisfied. It was only after I finished my studies that I began to find things that I felt I could relate to, and I think it had to do with coming across Florian Beigel’s work, which at that time was very important in Britain.

Adam and I both worked for what you could call high-tech architects. I worked for Richard Rogers, Adam worked for Ian Ritchie. In fact I worked for a number of practices including Jeremy Dixon. When I came across Florian’s work, in particular his project for the Half Moon Theatre in East London, it seemed to me that I had found an architect who was making work that in a small way had a political dimension, as well as a real interest in how you make architecture. Adam perhaps had the same thought, so we had somehow converged.

JM: Beigel introduced the political dimension in your architecture, didn’t he?

AC: I think I was a bit more aware of it than Peter because my education was different. When I was at school in the late seventies, early eighties, history was a big thing. At the Bartlett University you had decent history teachers, didn’t you? But you didn’t take much notice.

PSJ: It was a time in London when that wasn’t considered very important. In fact general studies at the AA was so unimportant you did not have to do it in order to qualify. You’ll find in my generation, the majority never wrote their thesis.

AC: At my school, which was a conservative school, although the students were very good and ambitious, the two biggest things were history and drawing. We had a fantastic lecture series, organized by Peter Rose, which was for the whole city but which took place within our school. People like, Rossi, Stirling, Eisenman and Venturi were invited. Those were the people we were really looking at. After each lecture our drawings would take on a new character! We had a fantastic scholarship at my school that you could get after your third year, if you had good enough marks. I went to Spain for five weeks, with a professor who had grown up in Madrid. This was in early eighties. My girlfriend and I then stayed on in northern Italy for two and a half months and London for a month. We saw a lot of Scarpa, who wasn’t yet well known. It was the year (1984) of the big exhibition at the Accademia in Venice. We also saw Rossi’s works and I remember thinking, why bother doing new architecture, old architecture is so amazing. After this travelling my diploma project started out kind of medieval, but in the end became more reduced, more correct. I was looking at John Hejduk, that big book, The Mask of the Medusa, had just come out and I was struck by the idea of meaning and form having something to do with these amazing drawings.

My diploma project had a lot to do with construction. Some of my professors were deeply dismissive that I was wasting my time doing things like half-scale brick details. I didn’t know what the details meant but I was interested in how the bricks went together and the idea that you could make a beautiful drawing out of the assembly of these parts.

AF: So, when you both finally found each other at Arup Associates, working in the same office, apparently you didn’t have much in common.

AC: Well, we both had worked for Florian [Beigel] by then.

PSJ: It was at Arups when our conversations began. We started talking to each other as a relief from the projects that we were working on. By that time we’d been working in offices for a number of years. I was certainly interested in trying to start out on my own, and I think Adam was as well. You don’t need to know us very long to know that Adam and I are very different, but we found ourselves, in our conversations, to be very complementary. One reason that I was looking to start on my own was because I felt I was a very bad employee. I was good at certain things but I was not a very well rounded employee. I wanted to find circumstances where I could concentrate on the things I was really good at, designing. Eventually we decided to take on a private commission that had been offered to us by one of the engineers in our group.

AC: You could have been a director at Arup, I was the one who used to go to work wearing shorts. One of the reasons I felt I had to leave was that we had started to get more responsibility, and were starting to threaten the status quo. We were trying to do good Arup buildings, but this threatened the current directors, because we were looking back ten or more years to when the work had a solid constructive basis.

PSJ: We’d been looking in the archives, in books, for projects that the practice had started with, projects in the fifties and sixties, and we went to visit these buildings and we’d photograph them, and bring the photographs back to the office. So we were beginning to embarrass the new directors, who were totally uninterested in that legacy and were trying to take a different direction. It became difficult. More importantly, I think, we were impatient and we wanted to have independence, and at that time we were being offered opportunities to teach. We managed to make an arrangement with the Polytechnic of North London, now called London Metropolitan, where we were both offered part-time teaching jobs, which was very good for us. It was a modest financial basis on which we could then make our practice, and the school was very close to my house, where we started the office. We were able to combine the teaching with doing competitions and some very modest early commissions, which was the way we survived for the first five years.

AC: Not so modest, every commission felt like it had a potential.

PSJ: The point was that they were small but we put such a huge amount of energy into them that they became very big in everyone’s imagination, even in the client’s imagination.

AC: It was good timing in that there were a number of competitions, like Nara and Yokohama. Five years earlier there wouldn’t have been any competitions that a young British practice could enter. And because of success in those competitions, we could get short listed for things like the Foyer in Birmingham.

PSJ: At the Polytechnic of North London, where we were all teaching, Florian [Beigel], myself, Adam and others, there was a very good atmosphere amongst colleagues, there were good design teachers, good historians, and good heads of school, Micha Bandini, and then Helen Mallinson. There was an enormous amount of energy that was coming out of the production of the teachers, in competitions and small projects, but also in the work that was being done by the studios and the exhibitions that were being made. It was a time when everyone was helping each other along a lot.

AC: You would have a jury and invite another teacher who wasn’t necessarily interested in the same things, but there would be a mutual respect. So it wouldn’t be about destroying the agenda of the other person. It would be about giving another point of view in a positive way. It was a unique, supportive atmosphere, very different to the AA for instance, where the units were so atomised. The students really appreciated the energy, and when you had a jury or a lecture all the students would be there and would participate. That is when North London became a special place, and it’s still a good school.

AF: Do you remember how you faced everyday practice at the beginning?

PSJ: I remember sitting down with Adam and telling him that my wife’s sister had a barn on the Isle of Wight that they wanted to convert into a house, and I was expecting him to groan and say, oh we can’t do that, that’s too ridiculous, but instead he reacted very positively. And we started talking about how interesting it might be to look at this building that had very thick stone walls, and we looked at the roof structure and imagined how we could make a new roof over this oak frame that was not slate but that was something of a memory of the original. The conversation became fascinating, and you could imagine sitting down to work on this tiny project.

The budget was 55,000 pounds and we worked on this project almost exclusively for a year and a half, which we were able to do because we were living very modestly, and we were teaching. It was very fulfilling. We were keen to build and to make things, and through conversation the tiniest thing became fascinating. And that proved to be the right thing to do, as opposed to trying to build up a practice by accepting small jobs in order to keep yourself financially stable. If you do that, the difficulty is that there is not enough benefit from the production of the work to expand your practice intellectually. So, it was having this kind of conversation amongst us, of the fascination of building, I think, that made these small projects so important. And that habit of approaching every problem very, very carefully and making sure that the result was as enriching as possible, meant that we developed a way of working that was very fastidious and time-consuming, and that you just had to say no to things that you didn’t have time to take on.

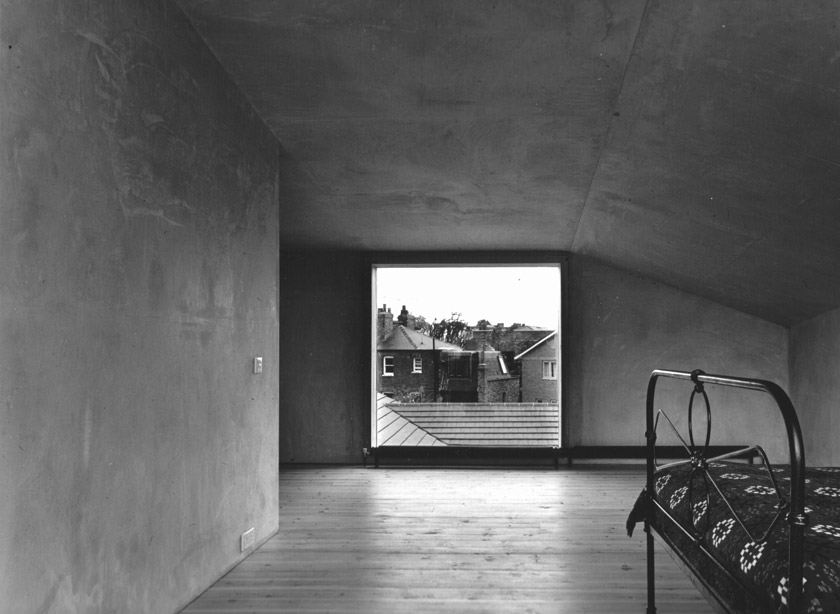

North London Mews House 1998

AF: Yes, but even if you do that at the stage of the design, later you have to go on site. How do you control the process at that point?

AC: It’s seamless. We are very organized, we know how much each job is going to cost us and how many hours it will to take. Every stage is time-consuming for us, and even though our working drawings are very complete, on site is still full time for at least one person for the duration of the project. Building is always a huge compromise, even though we don’t compromise very much.

AF: How was your experience at Walsall?

AC: We were under a lot of pressure because it was our first big project and we were working with a big contractor. There were many arguments and in most cases we won. They were not used to an architect arguing about construction so much, and they would try to argue that what we had drawn could not be built. But we were usually able to prove that our details, although challenging, were based on reality and on an interest in building. We draw things that are possible. They’re difficult, but possible. It is curious, because high-tech architecture is so much about a rhetorical display of construction and our architecture, like the stair at the Gagosian Gallery, is not. You don’t look twice at that stair, but it was very difficult to build. It weighs eight tons, and came in three pieces that were finished on site. Usually it is one of us that will push these things in the office, and makes sure that they are done. And as you get busier there’s a danger that one pushes less. I guess I’m always banging on the table. It is not about noticing the details, but about the energy that they give to the project. Something about construction that you can’t describe, is affecting. That is what architecture can do, because it’s physical, it is reality, and to me that is the way that architecture can be resistant.

AF: Resistant because it is material?

AC: Yes! I am interested in computers and the web and the way that the web can organize and not organize information. But virtual reality is a different subject to reality. Reality affects you. It’s physical, even before you understand it, like art. Peter and I are both very interested in contemporary art, in its capacity to insinuate emotions. Why shouldn’t architecture work in the same way?

PSJ: But you should explain, because you slightly deviated there, why an interest in reality is resistant.

AC: Because of the market, I think current architecture is completely enmeshed with the global market. It is all about reducing the importance and the capacity of architecture. Where is the architecture in an office building? In the eighties it was maybe in the skin. But now, the architects who were masters of the skin are not researching the envelope anymore, they are just using standard curtain wall products. The architecture of office buildings used to be about efficiency, the net-to-gross ratio. Now it is not about that either. The new generation of iconic, office buildings are not efficient and do not provide decent office space. It is certainly not about urbanism because contemporary buildings are destroying the city. So where is the architecture? I’m not sure! Architecture has always been about engaging with reality and changing reality, about providing a framework within which life can take place.

AF: You had said that you’ve had good contractors and clients. Do they choose you or is it that you’ve been very lucky? I mean, most people would claim they’ve had the opposite experience.

AC: Well, the most common way we reject jobs is that we meet a client once and they never call us back. We usually know this will happen beforehand, and are relieved.

PSJ: That doesn’t sound like much of a rejection.

AC: We have resigned jobs because of people we couldn’t stand. You step aside, because there are other architects that would be more suitable and everyone would be happier.

AF: Is that very usual in your practice?

PSJ: We are not interested in just growing the office or employing people in order to be able to do anything that someone may ask you to do. We like to have a stable group of people in the office and we don’t like to lay people off. So occasionally we get asked to do things and they might be very interesting, but we have to say sorry. I think the reality is that we’ve never been inundated with projects, but we tend to do them so carefully that they fill the space that is available.

AC: But even when we had no work, like after Walsall, we passed work on. Work that was too small, like a small house that seemed too complicated for its size. We have passed work on to younger architects and they are very appreciative and so are the clients. I think it’s what you are meant to do. As you get older, you should not be doing jobs of a certain scale. That is a real problem in this country because nobody passes work on anymore, because big offices always need more work.

PSJ: You asked about clients and I think we have been lucky. We won’t work for people that we don’t like. But I think in the end we have very good clients because they really know what they want and have come to us for a particular reason. The competition process is a very high-risk strategy, but it means you only get commissions where the client has chosen you above all else.

JM: After Walsall did you feel that the ‘establishment’ began to approach you?

AC: Walsall has been good and bad in Britain. Because of a national obsession with novelty, we have not been invited for a number of projects because the client or the city did not want another Walsall. Other, probably better clients, realise that Walsall is only one of our projects, and appreciate how well that project worked in its particular situation.

PSJ: The good luck that we had in winning the Walsall competition was, that of all the competitions you would want to win, that was the one. Other competitions didn’t get built, or had the wrong kind of client. So it was an incredibly good piece of fortune that one particular project should have come up with a client having the dynamism to make such an unusual and ambitious thing happen. It was of some benefit to us within this country, but actually our reputation seems to be bigger on the continent. In Britain we are regarded with some suspicion, by many people, because they find our attitude a bit uncomfortable and they don’t always want to have to deal with it.

AF: Have you the feeling of being in opposition instead of having a position?

PSJ: You don’t want clients to come to you because they want another piece of your work. You want people to come to you because they know your reputation and they are interested in being challenged by the way that you work with them. And we have had some amazing clients in the last five years, people who genuinely are interested in engaging with what we do, and in challenging us. I think we have been frustrated, wishing for more success in competitions or that more commissions were coming in through the door, but actually when you look back on it, the slow way in which we have built our practice has been good. You feel as if the number we are at now in not just to do with the fact that there are lots of buildings being built, but because of a kind of accumulative interest.

AF: When I said opposition I was referring to the international scene, where institutions and politicians demand a kind of architecture that is more…

AC: Spectacular?

AF: Yes, spectacular. And it is in this sense that I would like to know if you have the feeling of being in opposition.

AC: I think we do have a position, that there is some ethical potential in architecture. Construction and longevity is what makes architecture have a different capacity than fashion. I am interested in fashion, I am in awe of the fact that fashion designers can design so many collections in a year. But now, even in architecture, there is the eager expectation of what comes next and of the spectacle. Even the big stars who only six years ago were critical of this, are now converging. The work is becoming indistinguishable. So, what’s the next thing going to be?

AF: How do you stick to your position when you are involved in a competition and you know that the client demands something spectacular?

AC: We talk about that and our best schemes are more energetic and less dour. The Ascona project, for example, is quite spectacular, but rooted within the body of architecture. Making form is the core of what we do, but we are interested in forms that have something to do with architecture, with the architectural culture of particular places

AF: Aren’t you tempted to follow the trend? Even good architects follow trends and are anxious to be up to date. JM: Do you take one step forward in each competition or do you maintain always the same idea of balance of form, materials, the situation of the building within the city, etc.? Or do you push a bit forward to produce the more trendy building?

PSJ: I think we manage to avoid that push to make more trendy buildings. I think being a working partnership –and we collaborate closely in design– helps that. I think we can push each other, we can also stop each other. I think although the work changes, this balance that you talked about is always there. It has to do with the buildings being formally rich but not too much, about it having a kind of reference that is communicative and familiar while also being strange. That is something consistent. As you become more mature, your range and your ability to refer to things becomes richer and wider. But I think there is always a consistency. I don’t think we’re becoming less serious. I think we’re just the same as before. And I’m amazed to see, looking at fifteen years of projects, how the major themes were there in the very first project. The opportunities are different and the places are different but you’re still working with the same ideas, it’s kind of limitless. And of course you’re looking at the magazines and looking at what other people are doing, but the most important thing is that you concentrate enough in order to find things that are entirely your own.

JM: Do you try to add ambiguity to your buildings? Do you try to add intriguing elements to the familiar and ordinary scenario?

PSJ: I don’t think it’s a question of adding. I think it’s entirely a question of where the design goes through our conversation. And I think you’re looking for a certain tone in the character of the work that you arrive at, which is different in each situation.

AC: In Ascona we were trying to be spectacular –we talked a lot about that– but not necessarily trendy spectacular. The most spectacular buildings I have been to are not new buildings. The Guggenheim in Bilbao is spectacular, but not as spectacular as the mosques in Istanbul, or a number of cathedrals I can think of. The Hagia Sophia, a building that is sixteen hundred years old is so big that it feels like it has its own weather system. It is very moving, and not a lot of new buildings manage that. But often, one needs to be a Baumeister (in German, master builder) and do the correct thing. That is as much the role of the architect as to produce rhetoric.

PSJ: Baumeister in that it avoids spectacle?

AC: Some projects do not need to be rhetorical but should be about building. In housing for instance, there is no need for rhetoric. If you’re doing twenty apartments, they need to be good and correct. The design should have a lightness that makes the lives of people who have to be in a difficult part of London a little bit happier. But rhetoric in that situation is ridiculous, because after five minutes it will wear off.