I.M. Pei Interview (transcript)

Saturday, June 12, 2010 at 4:42AM

Saturday, June 12, 2010 at 4:42AM Via www.archrecord.com

JUNE 2004

Modernism's elder statesman looks back over 50 years and forward to finishing new museums on three continents

By Robert Ivy, FAIA

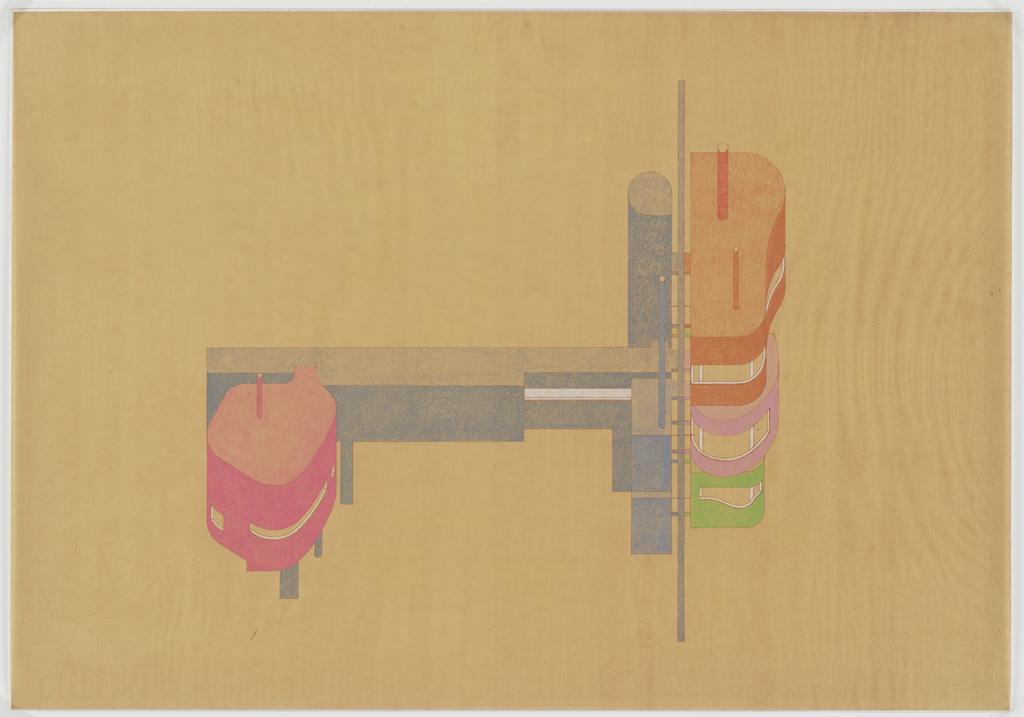

I.M. Pei's agility with the Modern form has garnered him prestigious commissions for museums and cultural institutions throughout his career, from the East Building of the National Gallery of Art (winner of this year's AIA 25 Year Award) to an addition and renovation of the centuries-old Louvre to a new wing for temporary exhibitions at the German Historical Museum in Berlin (pictured at left). Although he's been officially retired for more than a decade, Pei still has projects on his plate and a twice-a-week-at-the-office habit. Shortly after the AIA Accent on Architecture dinner on March 3 in Washington, D.C., editor in chief Robert Ivy visited Pei at his office in Lower Manhattan, where they discussed the evolution of Pei's design thinking, the importance of working abroad, and his current slate of projects.

AR: You say you have retired, but you continue to be involved in projects. What are you working on right now?

IMP: I haven’t taken any new projects in the past three years—I told myself, if I cannot live long enough to finish it, I don’t want it. So I have three projects now. The first one is the Musée d’Arte Moderne in Luxembourg, which is under construction right now. The museum will be located on top of an old, old fortress, Fort Tüngen, which the Austrians built in the 1800s. The client is the State of Luxembourg. I accepted the commission for the project in 1990 or 1991, after I retired, but it began only six months ago—it was stopped altogether five or six years for various reasons. The second project is a museum in my hometown of Suzhou, China. And I am also designing the Museum of Islamic Art in the Middle East, in Qatar.

AR: So do these projects involve design work, or development work and decisions about construction?

IMP: It’s a little bit of each. I just completed the design for the museum in Qatar, which I accepted about two and a half years ago. It’s now under construction, but that’s an exceptional one, because usually it takes longer than that. I’m doing most of the work on the Suzhou Museum on my own.

AR: That’s a very active, demanding schedule.

IMP: I’ve been active all my life. In 1990 I retired from my firm, I.M. Pei & Partners, and for two years I didn’t do much. Then I started to get kind of antsy, so I decided, I’m going to do some more work. And I chose to do work outside the U.S. because I’ve spent 45 years here and I wanted to learn more about what’s happening in the rest of the world. So I travel to the Middle East, I travel to China, I travel to Europe. It’s all very rewarding—the only problem is the travel is getting more and more difficult for me now. Ten years ago I would have enjoyed it a lot more.

And my projects have typically taken a long time to complete. Buildings might take on average about five to seven years to finish, but in my case it’s been longer, because the projects I have accepted within the past 15 years have been mostly government projects, and those involve some politics and funding issues, and approvals and so forth. So they’re slower.

AR: Tell me about the museum you’re designing in your hometown in China.

IMP: When this commission came, it was very special. I was born in Suzhou, a city not very far from Shanghai. It’s a very interesting town—there is a long artist’s tradition there, especially during the Ming and Ching dynasties, which produced many, many scholars and painters and so forth. That’s where my family lived for 600, 700 years. When the mayor first came to me about designing a museum, I said no, it’s too far away. They invited me to go back six or seven years ago, and I always tried to say no. But finally, a couple of years ago I accepted it. The location could not be more exciting. It’s a very special site, surrounded by a wonderful garden. I thought the project would touch on my relationship with my past, my ancestors, my old home. The building is now under construction. It has two more years to go before it’s complete.

AR: How about your other projects? Say, the museum in Luxembourg?

IMP: That project came to me after I had completed the Louvre. I was approached by the prime minister of Luxembourg and asked to design a museum for modern art, near the fortress [Fort Thüngen], which is being turned into a museum as well. It wasn’t as big of a challenge as the Louvre, but I was very interested in it. For instance, I wanted to know why the building would be located on top of a fortress. Luxembourg was and still is today a crossroads, the place where Germany meets the rest of Europe. The country lost part of its territory to Belgium in the 1800s, and during World Wars I and II the German military overran it. The fortress was the natural symbol, the physical symbol of the country. Very few people have visited Luxembourg—when I went there and looked at it, I said, my God, it’s built on a rock. And within the rock they had a castle, and within the city there’s a network of tunnels so the residents could move around and defend themselves. That was of great interest to me. I was curious to know how Luxembourg remained an independent country—that’s why I accepted the commission.

AR: Let’s go back and talk about a few of your past projects. Your work at the Louvre represented one of the first instances of an architect being employed by a major government agency in a way that gave you a prominent role in the country’s self-image. Could you talk about that? Were you consciously aware of how important the Louvre was to them at that time?

IMP: It was a total surprise that they approached me to do the project. You know the French, not to mention the Parisians—they see the Louvre as their monument, so to come to an American for a project like that is something I never expected. I thought perhaps they were just trying to show interest in different architects to try out the idea. But when President Mitterand asked me to see him, I knew that it was serious. Mitterand was a student of architecture, he had done a lot of research before he called me. He said, “You did something special at the National Gallery of Art in Washington—you brought the new and the old together.” But John Russell Pope finished the West Building in 1941, so when the East Building opened it was only about 40 years old. But the Louvre is 800 years old! A much bigger design challenge.

I didn’t accept the project right away, excited though I was. Instead, I told Mitterand that I needed four months to explore the project before I could accept it. I wanted that time so I could study the history of France, because what is the Louvre? The first portions were built in the 12th century, and a succession of rulers came, added on, built something, demolished something else. For 800 years the Louvre has been a monument for the French—the building mirrors their history. I thought by asking him for this time it might make him say no, thank you very much, because he was in a hurry—he’d been elected in 1981 and his term would last only seven years, and this was 1983—so there was some pressure for him to accomplish something.

In those four months, I studied. I asked for four visits to the Louvre, one visit each month. And I asked the Louvre to keep things confidential at first, without revealing the fact that I was asked by the president to be involved, so that I could go to France unencumbered and visit the Louvre, assess what’s wrong with it, what’s right about it, what had to be destroyed or must be saved, that sort of thing. Mitterand agreed to all this. You cannot defend your design without knowing what you’re designing for. When I was being questioned by the press about the design later on, all this preparation was very useful.

AR: The scope of the Louvre was so vast. You literally went through layers of history as you exposed and joined its lower levels, as well as designing an immense addition, and all with as little disruption as possible to the institution. No one ever focused on that—everyone just talked about the glass pyramid.

IMP: You’re absolutely right. Everybody points to the pyramid, but the total reorganization of the museum was the real challenge. Mitterand understood that. Few people know, for instance, that the French Ministry of Finance used to occupy the Richelieu Wing [north wing] of the Louvre. Mitterand was very aware of the importance of the Richelieu Wing, because without it, the Louvre is just a long

L-shaped building instead of a U-shaped building. Soon after he became president in 1981, Mitterand commissioned a competition for a new building for the Ministry of Finance in Paris. That gave him justification to move the agency to a new location, and therefore enabled us to claim that space. Without it, I would not have been able to do the project. I probably would not have accepted the commission—I could not have done anything for the museum.

And the biggest challenge of the Louvre was beyond merely architecture. When I first went there in 1983, it was divided into seven departments, and each was totally autonomous. The department directors would not even talk to each other. They were very competitive for space and money. So, architecturally we had to change this situation—make seven departments into one and unify them as a single institution. I’m not so sure Mitterand realized how big a challenge this was; I certainly didn’t. But the result worked out. Today the departments are all unified under one president, and they’re also unified architecturally. The fact that people don’t realize this huge challenge of the Louvre is totally mind-boggling to me.

AR: Let’s discuss form for a minute. We talk a lot about form—it dominates the discussion of architecture in the media these days. You yourself are a master of form—the East Building of the National Gallery, for instance, is a superior example of your skills, as the AIA recognized this year. But everything you’ve talked about so far is about the programmatic, complex, deeper issues that reside within projects. How do your formal skills interplay with this programmatic thinking?

IMP: Ever since 1990, I haven’t been all that interested in form, not at all. To create a work of architecture that looks exciting and different is not the challenge for me anymore. The challenge is for me to learn something about what I’m doing. I’ve been more interested recently in learning about civilization. I know something about the civilization of China, with my background, obviously, and I think I know something about American history. But that’s about all. And I’ve traveled all over the world, and for a long time I didn’t know very much about it, really. When I got the opportunity to do the new wing [the Schauhaus] for the German Historical Museum, for instance, I didn’t see it as an opportunity for my own ego, to do something so exciting that every architectural publication would want to put it on the cover. I accepted it because I knew it was going to be a very difficult project, and I wasn’t sure I could do something exciting there. Originally the building was to have been located near the Reichstag, a very prominent site. But ultimately they decided to site this tiny little building behind an enormous military museum [the Zeughaus] dating from the early 18th century, which is very Prussian. I visited that museum, and you’d think that any collection of military artifacts would be all guns and cannons and whatnot, but there’s a lot more than you’d expect there—a lot about Prussian history, which of course is the foundation of Germany. [The Zeughaus, a weapons depot before becoming a museum, is now undergoing renovation to house the permanent collection of the German Historical Museum]. This location has much less visibility. I had the idea to do something helical and transparent with the new wing, something that would be symbolic of the unification of East and West Germany. The prime minister personally asked to see some sign of this in the building. When you’re asked that by a client, it’s an opportunity you just don’t waste. So, while it was an exciting challenge, form-making is not the reason I’m still engaged in projects. One of the reasons I took this on was that I wanted to find out as much as I could about Germany’s architectural history. The name that kept popping up was Karl Friedrich Schinkel. I’ve seen his museum, the Altes Museum in Berlin, but I hadn’t visited any of his other work until I began designing the new wing. I think his greatest skill was the diversity of projects he achieved, from the very monumental, like the colonnade at the Altes Museum, to the small, domestic skills he brought to the villas he designed in Berlin and elsewhere.

AR: How did your museum project in the Middle East come about?

IMP: How do I begin? Qatar does not have much history, it’s a new emirate. So I couldn’t draw on the history of the country; its history is really just being a desert. But I thought, the one thing I must learn about for this project is the Islamic faith. So I read about Islam and Islamic architecture, and the more I studied the more I realized where the best Islamic buildings were. At the beginning, I thought the best Islamic work was in Spain—the mosque in Cordoba, the Alhambra in Granada. But as I learned more, my ideas shifted. To begin with, the climate of southern Spain is not at all like desert, where most Islamic architecture is built. I kept searching. I traveled to Egypt, and to the Middle East many times. I saw early Islamic architecture in Damascus, Syria, where they took some early Christian churches and transformed them into mosques, so they were not pure Islamic—just as in southern Spain, it’s no longer pure Islamic architecture either, because it gets mingled with Christianity. Or in Turkey, where the Ottoman influence is felt, too—it’s Islamic but not pure Islamic.

I found the most wonderful examples of Islamic work in Cairo, it turns out. I’d visited mosques there before, but I didn’t see them with the same eye as I did this time. They truly said something to me about Islamic architecture. The museum I’m designing is more influenced by the Mosque of Ibn Tulun than any other building. This mosque is very austere and beautiful, its geometry is most refined. You think of Gothic architecture, it’s so elaborate. This is the opposite—so simple.

AR: It’s inspiring to see that you’re so engaged with these issues. You’re still a student!

IMP: Yes, I am. You always should be. That’s what makes life interesting.

AR: We’ve talked a lot about museums, but there are other building types that you’ve been involved with. The Bank of China building, for instance, in Hong Kong—a tall building. The issues you faced with that project are a very different set of concerns from those of museums, aren’t they?

IMP: That’s very true. Actually, many of the projects I’m most proud of are tall buildings, especially the housing projects. In New York I have two: one in Kips Bay and one at New York University. At that time, those projects were most challenging, architecturally—how do you enable redevelopment, foster urban renewal with a tall building? For Kips Bay, I had a wonderful client, William Zeckendorf, who was willing to gamble with me on using concrete and not brick for a high-rise apartment building. That was very innovative at the time.

AR: How old were you when you got the Kips Bay project?

IMP: I came to New York and worked with Zeckendorf in 1948. I was 30 years old. Kips Bay came to me two years later, in 1950. Later I got my first museum project, the Everson Art Museum in Syracuse. That was about 1960, 1961. I was very busy back then. You don’t really get a chance to do anything until your mid-40s. I told my sons that: Don’t expect to accomplish too much in the early part of your life. I was fortunate—after the war, I left China, in 1944; there was nothing going on for me at the time. I went back to Harvard to teach and to get my master’s degree. I thought teaching would give me the most flexibility in case I had to return to China to be with my family. I didn’t really practice architecture until I got to New York; I didn’t have many qualifications or much experience at all. Becoming a designer is a long process of learning. You make mistakes when you’re young. It’s important to have the opportunity to make mistakes.

AR: What are your days like when you’re not at work?

IMP: At home, I have a wife, fortunately, and my children are all grown, and I have many grandchildren. I spend weekends with my grandchildren; I adore them. On a daily basis, my home life is very simple. I spend about 2 hours every morning reading the newspaper. As my two assistants will tell you, I don’t come to work in the mornings, for two reasons. First, I want to be informed—that means I go through The New York Times every day, and then I watch some news on television. The second is, mornings are the best time to communicate with my clients abroad. So I communicate with Luxembourg, with Berlin, with Paris—I continue to do work on the Louvre, it didn’t end in 1993. So I’m on the phone a lot to my international clients in the mornings, after I get through the news.

Two afternoons a week I come to my office. If I’m not here, I go to my sons’ office. I still have two of my projects working through them—the Museum of Islamic Art in Qatar and the Suzhou Museum.

AR: Did you do any conceptualizing for the redevelopment or the memorial in Lower Manhattan?

IMP: No. That project probably will take 10 years, and I didn’t want to think about a project that I couldn’t finish. That’s a kind of temptation. It was the same reason I declined to submit an entry for the U.N. addition in New York, the one that [Fumihiko] Maki is now working on. I thought I wouldn’t be able to finish it. One has to realize one’s limitations. Why kid yourself?

I.M. Pei in

I.M. Pei in  Interview,

Interview,  Transcript

Transcript