aecworldxp put up this interview recently.

by Sarita Vijayan

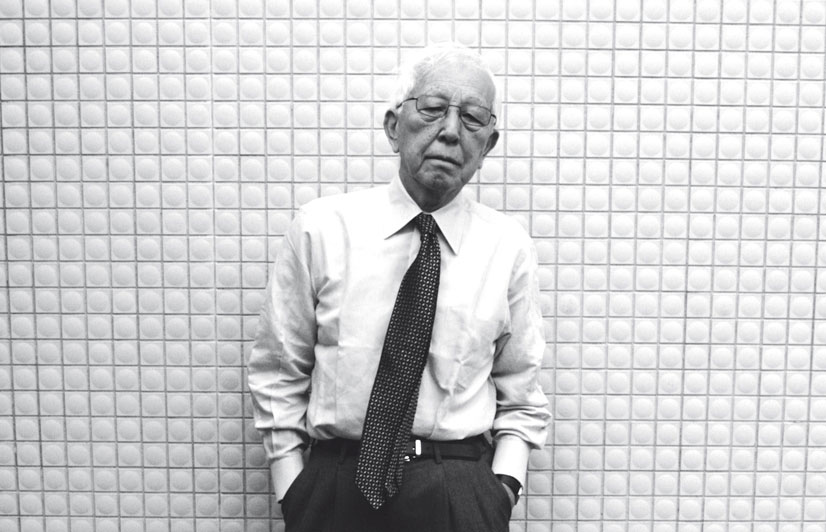

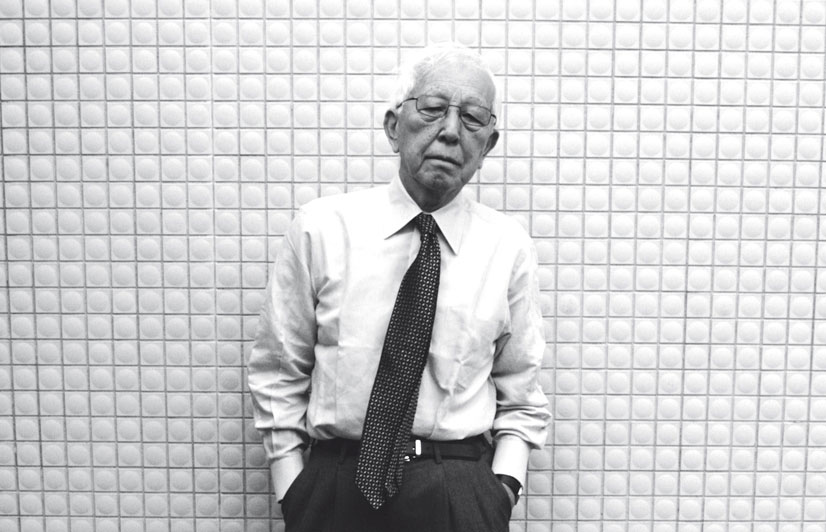

Fumihiko Maki is the Pritzker Prize winning Japanese architect who is recognised for his architectural and urban design work as well as his contributions to architectural theory. He is known for his rational approach, intelligent combination of technology with craftsmanship, and delicate details as are illustrated in his projects. Fumihiko Maki is one of the few Japanese architects of his generation to have studied, worked, and taught in the United States and Japan. Following Fumihiko Maki's architecture studies at Tokyo University, Fumihiko Maki obtained master of architecture degrees at Cranbrook Academy of Art (1953) and the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University (1954). Fumihiko Maki worked with Skidmore, Owings and Merrill in New York (1954-55) and with Josep Lluis Sert(Sert, Jackson and Associates; 1955-58) in Cambridge, Massachusetts before establishing Fumihiko Maki and Associates in Tokyo in 1965.

A member of the Metabolist movement - a group of ambitious postwar Japanese architects who advocated the embrace of new technology with a concomitant belief in architecture's organic, humanist qualities since 1959, Fumihiko Maki remained at the fringe of the group, concentrating on space and the relationship between solid and void and not on schemes for entire cities based on industrial technology.Fumihiko Maki's attempt at dealing a public architecture in Japan, where such a concept traditionally did not exist, is obvious in his sports and convention facilities. The expressive stainless-steel roofs of the Fujisawa Municipal Gymnasium (1984), the Tokyo Metropolitan Gymnasium (1990), and the Makuhari Convention Center (1989 and 1998) assure these buildings of a strong presence in the city.

INTERVIEW

Q. How do you interpret traditional Japanese architecture into your own work, especially in contemporary times?

A. The traditional Japanese architecture was influenced by wood and this is reflected in the shape of the roof, the treatment of the wall and other elements in the building. Today, architects use different materials like concrete, glass, steel etc. In Japan, we have a traditional way of spatial management which can be reinterpreted in contemporary times for instance using the transparent/ translucent materials like shoji screen. It is an experience of sensing the space around us although we might not able to see through it. We are also interested in making people experience sequential encounters with spaces. Here, there is no demarcation made by the wall for example in the crematorium, the interconnectedness is not by doors but by how differently one space is treated from another. The Japanese are conscious of the interrelation between interior and exterior spaces. There is also this tradition of using the natural light, which can be reinterpreted in modern buildings as well. We are not afraid of dim and small spaces but always try to make people comfortable even in such spaces. So, there are a number of ways to interpret the Japanese spatial systems and attitude towards space.

Q. Japan, like India has a strong traditional legacy but designers are constantly trying to ape the west. What are your views on this disconnection?

A. There is a disconnection but we must not be afraid of confronting it. We need to have open horizons and the most important thing is not just how the past can be reinterpreted but how to maintain the continuity from the past to the present.

Q. What changes have taken place in architectural practice from when you started till now?

A. For one, our society is becoming more interested in environmental issues. In the beginning, there used to be some mention of sustainability but today it is important for architects to consider such issues. At the same time, the practice itself has become complex 50 years ago when I started, there was a client and he wanted the architect to design and when the project was over, we delivered it to him. Today, we have to deal with a number of things the city, the people to explain the project there are many more voices besides the client’s. We used to have a simple way of designing structural and mechanical engineers and a cost estimator were involved but today we have cold consultant, curtain wall consultant, kitchen consultant. It is as if the responsibility and the liability must be spread out to avoid the consequences. But the authority of the architect, unlike in the past, is getting diluted there is a fragmentation of practice which has made the process complex. I think architects must have trust in people in order to keep their integrity for the profession.

(Spiral House, Tokyo 1985)

(Spiral House, Tokyo 1985)

Q. You have achieved so much – what is the driving force for you to continue?

A. For me it’s not just about pleasing a client, but also what is important is a good response from the public. When I did the crematorium, lots of people not only visited it, but also expressed their desire to be cremated there. This was the highest honour for me and is what drives me even at this age.

Q. How do you balance the silence with the dynamism in your buildings ?

A. I don’t like a building to speak too much so I design the space to be comfortable. As architects, we should be careful for choosing and combining material to make them converse among themselves. It is like music – you use a number of elements but at the end they have to produce a harmony. This could have produced the building little quiet and also interesting.

Q. Your buildings though organic in nature are placed in cities, which are linear.

A. Architects are given different site conditions. Whenever you do buildings outside cities in rural area you are free to do what you want. But within a city they have to be a part of the fabric. You need to be sensitive for that. So the first thing we do is make a model of the surrounding – an empty hall produced by surrounding buildings and artefacts from this we are able to bring out some images on 3D form and space – befitting to the place and also produce its own identity. Sometimes in Japan, we have a difficult site – a highway in front and bulky building around it – when we did Skyrock in Tokyo this was the situation. Making a model of the surrounding is the first step in coping with last step.

Q. What or who is your source of inspiration?

A. I have no inspiration just hard work. When we form a group for a project – we start the discussion about the important issues and by hard work there is more chance to have inspiration -both small and big.

Saturday, October 30, 2010 at 6:49PM

Saturday, October 30, 2010 at 6:49PM  Fumihiko Maki,

Fumihiko Maki,  Norman Foster,

Norman Foster,  Richard Rogers in

Richard Rogers in  Video

Video