Entries in Raimund Abraham (6)

Raimund Abraham: Logos Interview

Monday, June 14, 2010 at 7:33PM

Monday, June 14, 2010 at 7:33PM Another interview with Raimund! via logosjournal

A Conversation with Raimund Abraham

with Gregory Zucker

Q: Earlier, we spoke about the difference between architecture and “buildings”. Could you explain what you meant?

A: I consider architecture a discipline, not a profession. Considering the classic periods of architecture, architecture was more or less confined to the sacred and political power. Architecture represented a spiritual device and now it is considered that it should merely ornament our lives.

I think the major break in history occurred at the beginning of the twentieth century. When the old social or the known social structures collapsed: no more monarchies and a new society emerged. With that new society entered an evolution in technology. You had new programs so architecture became synonymous with the new ideologies and the power of the worker in work more than celebrating the sacred, so, for example, you had the factories and workers’ housing. Now it appears that almost any domain can be expressed through architecture. Maybe this is true. Yet, for me architecture’s role is to elevate the profane with the sacred. If you succeed in making architecture, the sacred has to prevail. That means that in the most profane or the most pragmatic program, the program always has to succumb to this period of the sacred whether it is a small house, a cathedral or a temple.

It is the nature of making things which I believe is the true foundation for any artistic discipline, whether it’s film-making, architecture, painting, or sculpture. This whole “making” is challenged by new technology. The technology is totally divorced from the “making” because ultimately you make things with your hands. When I met Jonas Mekas and other experimental filmmakers, I was inspired by the idea that you only need a camera to make a film. Similarly, you can reduce the making of architecture to a piece of paper and a pencil. Even if I don’t build, when I make an architectural drawing I construct it so I always anticipate the physicality, the decay, the atrophy of material in the metal so this has to do with making. There’s incredible precision. The beautiful mystery of architecture is rooted in the precision of how to put one stone on top of the other. It’s not the stone itself; it’s the cut in between the stones, the seam. The precision of the emphasis is the principle of structure. How they are joined or how they are divorced.

As an architect it is very important that you distinguish between different realities. There’s the reality of the drawing and the reality of the building. So one could say, or at least it is the common belief that architecture has to be built; I always denied that, because ultimately it is based on an idea. I don’t ever need a building to verify my idea. Of course, what with a building is more its vanity and actual physical experience. But I anticipate; I wouldn’t even build it if I could not anticipate how it would be.

Q: Once the building is actually built the public is forced to deal with it. How should architecture relate to the public?

A: It has to relate to program. Without program you can’t have architecture, but the program has to be translated; it has to be challenged by the ideal of the discipline. So the program can never dominate. It’s a conflict, which, of course, does not exist in film because film is done and then it is shown to the public. It is self-contained, while architecture is not because when it is built it is the offered for use. It all depends on how you define “use’” philosophically. ‘”Use” can either be a celebration of function, which ultimately in its optimal implication would be a Fascist result because it would be completely covered by how the program had been implemented. So in architecture I think the program has to be reinterpreted. Even on a very basic level. For example, when the artists discovered the lofts in New York, completely new ways of living were offered because they had universal space. If you compare loft-living with an apartment where you have an entrance, you have a living room, a bedroom, and a bathroom, your life is defined by the nature of the rooms. Thus, the more, I’d say, bourgeois inhabiting those spaces becomes. It’s more oppressive because then life becomes a habit and I believe that architecture has a role of challenging that habit at all times. It becomes a creative force in your life. Architecture has that ability, otherwise it would just be too oppressive, too influential, and perhaps it would dictate the way you behave in space.

In order to build something you have to violate the site. You dig a hole in the ground, which means you violate. That’s why the Indians only build teepees or build their permanent structures of stone on the rocks and never violated out of respect for the earth. So there is this conflict between the structure and the site. The reconciliation is that you create the formal conditions, a new equilibrium. The equilibrium you have intervened into and disturbed has to be reconciled. That is really the role of architecture.

Q: And what about your project in China?

A: Like many other sites in China, they have erased all traces of what was there before. So I had to create my own memory. Instead of intervening in a landscape, as I discussed before, I had to imagine the block, with houses, whatever function it had and then I carved into the block. So the block became actually an extension of the earth. And then of course the challenge was how to geometricize that. It was an emotional act from the first moment I held that chisel; that chisel bit the block, then I started to translate that emotional topography into a constructible geometric landscape. And so every single point in the landscape now is defined.

Q: I see, but you’re dealing with a culture that has a very long history of architecture.

A: This history is completely ignored by the present so-called ruling class. I feel like China wants to do, or is more or less successfully doing, what took the industrialized world, like America, a hundred years. They’re doing it in ten and, of course, there is a consequence. The culture is in danger. The only part of their culture that you can still sense is their food.

The real conflict is between the land and the city. All this progress, this obsession with reaching the top level of progress in industrialization in the world leaves all the peasants behind. Eighty percent of China is made up of peasants. This is also the lifeline for the country and there’s no program of how to cope now with that conflict of the poverty in the country and the new wealth in the cities. It’s apocalyptic out there. Beijing was a horizontal city, only pagodas, and the architecture was visible or reached above the horizon of the houses. Now they just have left a small portion of it, which is now being gentrified; its becoming like a SoHo and so that’s what you witness there.

Q: I am interested in hearing your critique of the project at Ground Zero, as well as hearing your explanation for the design you proposed.

A: There was no hope from day one that the commercial world would really go for an architectural gesture that would be as radical as the event they claimed 9/11 was. Instead of saying, “Okay, now Mr. Silverstein, let’s get you some architects to build the most efficient commercial buildings there,” they tried to cover their intentions by saying, “Okay, now we need architecture.” From day one, the project was a disguised commercial site plan. It is very clear that when the pragmatic force starts to dominate that process, they will do whatever they want and then more or less declare the imprints of the two commercial towers as sacred because of the original event. I think that is blasphemy. It’s a fake…you see that’s what I called it at the beginning: the necessity of architecture to celebrate the sacredness; this is just the opposite. It’s fake sacredness.

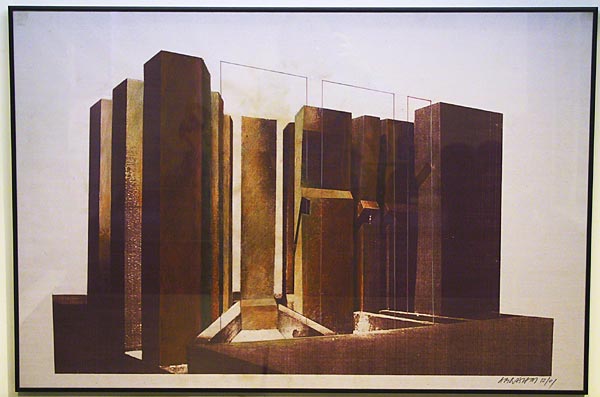

What I made was a metaphoric proposal. I just had three gigantic blocks which formed three walls, parallel walls on the side, and then I chose the moments when the event occurred, when the first plane and the second plane hit the towers. Then, when the first tower collapsed and when the second tower collapsed, simply as moments of an event. I located the sun vertically and horizontally for each of those time frames. I cut through those three walls in that angle of the sun. So, in a way, you caught the moment, a moment without any kind of a narrative reference. When you would be standing in that cut, at that particular moment in time, the sun would hit you. The architecture would celebrate and essentially revive that space and time, which became synonymous.

Ground Zero Proposal

Raimund Abraham in

Raimund Abraham in  Interview,

Interview,  Transcript

Transcript Raimund Abraham Interview with ACFNY

Friday, June 11, 2010 at 3:41AM

Friday, June 11, 2010 at 3:41AM I rode by the Austrian Cultural Forum today and thought about Raimund Abraham...so I'm going to post an interview with him and then search for one with John Hejduk. Here is an interview with Abraham back in November 2001.

courtesy ACFNY

Q: You recently said that irony is one hallmark of the Austrian personality. Can you elaborate on this from your perspective as an architect?

RA: It's practically genetic in Austrians. It's in their literature. Austrian literature of the 20th century especially is a document to irony. The great poets and writers always question the German language, not in terms of content but the language itself. So irony is a mechanism to question, to become a critical device. In its final formulation, irony has to disappear in one's work like any metaphor. Take for example the project Adolf Loos presented in the competition for the Chicago Tribune tower in 1922. His response to the problem, the inherent conflict between modern technology and the tradition of aesthetics, was to make the whole shaft of the skyscraper one gigantic Doric column. There was such a deliberate arrogance to his proposal! On the other hand, the column was executed to have so powerful a presence that the irony was not entirely predominant. The irony could be there and that is the potency of the work. Irony needs to be present but never clearly so. It's like tightrope walking for the artist.

Q: Do you walk that tightrope in your own work?

RA: Any artist walks the tightrope. When I am working, I try to eliminate speculation entirely. When I have completed the work, then I speculate about my own intentions like anybody else does. But the whole truth is only in the work itself.

As an architect I simply try to solve the problem at hand. My father was a winemaker. He just tried to make a very good wine. I look at bakers or shoemakers and I don't see that much difference between them and myself. I never liked the notion of "fine art." An artist is primarily a worker. Take Jackson Pollock: He was a worker. The action of his work became a new language of painting.

Q: How did this approach -- working without speculation -- play itself out with your design for the Austrian Cultural Forum building?

RA: When I started to develop my first ideas in the competition for the project, it quickly became evident to me that the smallness of the building would cause an incredible, almost inconceivable increase of cost. The Austrian Cultural Forum is a tower 25 feet wide and 24 stories tall on a site less than even 100 feet deep. These are remarkably restrictive conditions that demanded ultimate formal reduction. It would have been totally irresponsible to just engage in an architectural gesture of grandeur without trying to provide the utmost use of the building. That immediately became my problem to solve. Architecture is the only discipline within the arts that has to confront itself with the issue of use. And there is not one formal decision in the Austrian Cultural Forum building that has not been contested with use. The use in this case is a very dense, complex program on a site where the space is compressed laterally by surrounding buildings -- a compressed void. I had not only to confront use in terms of the zoning envelope, the general functions of a building, but also in dealing with gravity, with materials, with the physical world. As the architect you must translate your idea into a drawing, then into the physical world.

Q: What inspired your design beyond these specific limitations of the site?

RA: You never know about how ideas can come into being. Maybe from looking at the sidewalk or from what one has eaten for lunch. So I can't say what the inspiration was. But I can tell you what my intention was with the building: to resolve the extreme condition of smallness of the site, its void, its lateral compression.

Q: Among the 226 architects who competed for this commission, you were the only one whose scheme placed the emergency fire stairs at the rear of the site. This was a remarkable move that nevertheless seems so obvious in retrospect.

RA: This particular solution of a stair, which would satisfy the functional requirements as well as the directives of the building code emerged as a result of a rigorous and sometimes agonizing process to arrive at a solution within the severely restrictive spatial conditions. And at the same time this solution enabled me to transform an element of sheer utility into a decisive architectonic component. If there has been any inspiration or reflection upon a particular New York condition it was my fascination with the simplicity and surprising complexity of the scissor stair, which I believe was invented in New York City in the 19th century in courthouse designs in order to provide independent access and egress for prisoners, their captors, and their judges. Whether or not it will continue to function in that capacity I will leave to the future users. Architecturally it has become the Vertebra of the Austrian Cultural Forum tower, striving for infinity as does the endless column of Brancusi. Architecture ought to transform the profane into the sacred, that is its ultimate challenge.

Q: In attempting to resolve this essential conflict, in making ideas material and the profane sacred, is there a moment when construction -- actualization -- compromises your ideas?

RA: All this depends upon the ability of an architect to translate his own idea into built form. For example, if I talk conceptually about sheets of glass which are suspended and are more falling than rising, then I have to find materials and methods of construction that satisfy this condition when I build. If I don't succeed in that first, then I don't succeed at all, even if I have the most striking designs. I succeeded at the Forum building with the glass Mask because it achieves that quality of suspension. It expresses the condition of the site, the gravitational forces that are represented by what I call the three towers of the building -- the Vertebra of the stair tower on the north, the structural Core tower at the center, and the Mask glass tower, which is the curtainwall on 52nd Street.

Q: Must an architect actually build his ideas in order to achieve something "sacred"?

RA: I believe architecture doesn't have to be built. There are equally important projects I have drawn that have never been built. When you build, you enter the public realm and that is a different kind of architecture. I don't need to build in order to verify my ideas. But building is the most difficult type of architecture, I must say, because the whole process of translation is exceedingly complex. It engages you completely. You have to become a street-fighter, a lawyer, and a detective to succeed. It encompasses the risk to entrust your work to others for its final implementation.

Q: Is a perfect translation possible in the evolution from drawing to building?

RA: Perfect? No. Perfection is like truth. You can strive for it but you never reach it. Building in New York is extremely difficult. The architect has no true authority here and that is frustrating. The authority lies with the contractors, the builders. I'm just a war reporter on the scene every day. If it is true, what some critics claim, that this is the first real architecture to be realized in New York in 40 years, it would mean that for 40 years builders in New York have not been challenged to the highest degree of precision. You must have that precision to have real architecture.

Q: Returning to your comment that artists and architects are workers, why do you think we need to make distinctions that elevate artists above the status of worker?

RA: These are simply devices to make art and architecture easier to consume. The whole construction of history is simply a structure for people to consume the past. And history -- or about 99% of it -- is all wrong because there is no continuity in history. Every invention is a break in time. That's true of architecture as well of all other disciplines. There are influences obviously, influences that carry over. But the influences are devices of comparison and that comparison never provides a true critical argument. You cannot, for example, compare Frank Lloyd Wright with Le Corbusier. Each work can only redeem itself, illuminate itself. You can only take projects by one artist and have them confront each other, then see which one is stronger in terms of a detectable vision within the body of work of that individual artist.

Q: Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Director of the Austrian Cultural Forum, has described yours as 'a career without compromise.' How do you respond to that description?

RA: In terms of my own work, unwillingness to compromise is not a virtue. I simply cannot compromise because my nature does not let me. So I am lucky. But I observe that architecture in recent years has generally been promoted through stardom and spectacle rather than respect for structure, precision, and a real commitment to social issues. It was not always like this. Think about the pioneers of modern architecture of the 1920s and 30s. Architecture was then very much engaged in social issues. The most important projects of that time were either for workers -- factories, housing, churches -- or projects that identified cities, civic work. And now ironically it seems that just when art has more or less disappeared as a critical device in our society we have more museums than ever before and more new museum architecture. That's particularly interesting when you reflect upon the pioneer artists of the post-War era in America. They were so socially committed that they couldn't really separate their art and their own existence from being part of the larger society and engaging in critical arguments about the state of affairs of our society. In my opinion this has almost completely disappeared.

Q: Do you think the building for the Austrian Cultural Forum has a social or societal role to fill?

RA: In terms of what goes on at the building, I believe the Forum as an institution exists outside of the commercial world, a commercial world that is rather orthodox in New York nowadays. The Forum is autonomous from the power structure of the art world and if the director and the staff and involved outsiders can succeed in attaining a high level of quality in the programs, if they introduce work that is not part of the existing power structure, then the Forum could be a very, very unique place for this city and actually very influential. I believe they intend to be also an outlet for American and international artists working in collaboration with Austrians, a place for new ideas, new forms. If this is really going to be the policy and the practice of the institution, I will be extremely happy because then architecture has succeeded in inspiring and challenging its use.

Q: In the wake of the events of September 11th and the destruction of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center, there is a great deal of discussion and even debate about how architecture can and should satisfy the need for beauty while honestly acknowledging the dangers of modern life. But for years you have declared that beauty and danger are inextricably linked in architecture. Do you think such ideas take on new significance in these times?

RA: If I did not include the anticipation of terror in my architecture, it would not be worth anything. Ultimately you become conscious of your own existence and accept the truth we are born with: the knowledge that we are going to die. If such anticipation is not part of your spectrum of thought and feeling as an architect, your work is meaningless, without authenticity.

Adolf Loos wrote, "When you walk through the woods and come upon a hole two feet wide, six feet long, and six feet deep, you know that is architecture." This is what I am talking about. Death has to work, it must express itself and its meaning somehow just as do hope or desire. Maybe it's a problem of a technocized, urban society that death becomes very much removed from our lives. I grew up in a small town in Austria where there were funerals all the time. It was part of life.

Q: This was during the Second World War?

RA: Yes. And there were bombs, of course. I had horrifying experiences that shaped my aesthetics. I saw buildings disappear that were supposed to be permanent. I saw the entire sky covered with airplanes. But do you have any idea of what a beautiful sight that is -- an iron sky? It was magnificent. So in terms of the power of a moment of destruction, walking through the completely destroyed center square of our town as a 12-year-old was as monumental for me as what happened on September 11th here.

Q: What do you think we will build down there on the Trade Center site?

RA: Right now it's just too raw, of course. There are still several thousand people buried on that site. And the question of a monument, a memorial seems absurd. Think about the fact that no Holocaust memorial ever succeeds in the end because no monument can ever be more monumental than a concentration camp. For the most part these museums and memorials to the Holocaust are, for me, trivializations. It's always the case that the place of the actual horror itself is by far the more powerful manifestation of memory than anything you try to artificially impose. No building can match the terrifying empty spaces of these original sites.

Q: Can an architect ever really succeed with such projects? Can you build memory?

RA: No, you cannot. But you can build to evoke memory, to manifest absence. For example I think the Austrian Cultural Forum building will provoke different kinds of memories through association. You look at the building now in a particular way after what has happened on September 11th. Because of its iconic presence it evokes totemic qualities. Just recently I looked at the building and recognized a figure, a totem. This was not at all intentional. If I had planned to make a totem, a piece of memory, the building would not have the same strength. The inspiration for the design came completely out of seemingly trivial circumstances of the site, zoning, codes. And then other things triggered, unconsciously. I think the only time one is really conscious is when one works. When I work, I concentrate completely, totally on the problem at hand. When I draw a line, that is the most honest moment in my life. Everything else in my life may be confused, but that line is true.

Q: Drawing has been essential to your career, probably the dominant route of access into your thought process for other people.

RA: When I draw, the drawing is not a step toward the built, but an autonomous reality that I try to anticipate. It's a whole process of anticipation, anticipating that a line becomes an edge, that a plane becomes a wall; the texture of the graphite becomes the texture of the built. That is the dialectics of drawing. Now, when you translate the drawings, one also has to distinguish between the drawings you make in this autonomous process where the drawing is the ultimate reality. I draw first for myself, not for somebody who is building, which means there has to be an absolute clarity in my mind, and the ability to retain the idea that I've established in the drawing, and furthermore, the anticipation that this idea will be buildable. Of course, it's a highly complex process. I'm talking about the first stage, which is a dialectical confrontation of whether what I draw will be built. From the moment I know that something is going to be built, my drawings have become something else. And at that point I draw less, and build models immediately. One really has to distinguish between those different phases.

Q: Is recollection important? You grew up in the mountains of Austria. Do memories of those places of childhood have any presence in your architecture now?

RA: Yes. I even published a book called "Elementare Architektur" (1963) to celebrate these memories. It has just be reissued, in fact.

Q: What sort of house did you grow up in?

RA: In a house with a large garden and a view of the Dolomites. I spent a lot of time with my relatives in South Tyrol, which is Italy now. They had a huge farm and an inn and animals. I always identified more with this place, the birthplace of my father where we still grow wines.

Q: And now you are building a house in Mexico.

RA: Never in my life did I dream I would design a house for myself! But just in the last three years I have had the desire for a place where I could cook. And in this village in Mexico they have wonderful fish, so that is what triggered the idea for building a house there. Cooking is a device to define your home. Without cooking, without a hearth, you have no home. A friend of mine owns spectacular land there. We walked around and there was one very special place to which I immediately felt a special attraction. We walked further and a bit later encountered a sign that said, "You are entering sacred ground." There is a hill surrounded by ancient fragments of what must have been huge walls. The village does not even allow archaeologists to dig there and it is completely pure. I think it is the only manifestation of real architecture on the entire Pacific coast of Mexico! And it is the most southern point of the North American land mass. When I saw this site I knew I wanted it. It was meant to be. That was three years ago. We are beginning construction of the house in early November.

Q: Did you take the same level of pleasure in building the Forum tower that you are clearly taking in constructing the Mexico house?

RA: Well, the adventure of building in New York City is still going on. You are confronted every day with the enormous challenges of getting it right. I have to force myself to enjoy the privilege of building the Forum tower because as I have said, I do not look beyond the process or think about how it feels while I am working. So I suppose I don't really take pleasure in the building yet. I will take great pleasure when the building is in use, when programs and artists and audiences take it over, and when I'm celebrating the fact that I was finally able to give something back to New York City, which has been my home for three decades and is the city I love.

Q: Is the whole notion of presenting Austrian culture in America relevant to you? Do you relate to the idea of being an Austrian architect, an Austrian artist?

RA: Do I feel Austrian? Well, I was born there. Maybe childhood is the most important memory one has. Undeniably it influenced my personality. Am I Austrian today? I carry its culture, its sensibility. I am still an Austrian citizen. But I have no clue how Austrian my work is. I have become a New Yorker and maybe the memories of ones origins are reignited in a new place. And this place feels closer to me than the place of my origins. Except the work, everything is fluid, everything moves, everything changes, my work is my life and ultimately my real and only home.

I found this great photo of Abraham and Lebbeus Woods on Lebbeus' site. There are some touching stories told by students and friends of Raimund in Lebbeus' entry the day after Raimund died...one of which is from Anthony Vidler here....http://lebbeuswoods.wordpress.com/2010/03/04/raimund-abraham-1933-2010/

Raimund Abraham in

Raimund Abraham in  Interview,

Interview,  Transcript

Transcript Raimund Abraham: Bomb Magazine Interview

Thursday, June 10, 2010 at 3:42AM

Thursday, June 10, 2010 at 3:42AM Found this great interview Abraham with BOMB MAGAZINE...nice images of Cultural forum under construction.

2001, By Carlos Brillembourg

All images courtesy of Atelier Raymund Abraham.

INTERVIEW

Raimund Abraham is an architect who creates conditions that demand a viewer or inhabitant consider the origins of architecture. His discipline elicits a confrontation between the ideal—imagined notions of perfection—and the real—its physical counterpart. His architecture, anchored in the specific nature of its materials, questions and affirms the metaphysical realm. Abraham’s is a deliberate and precise investigation of architecture’s responsibility to be life-giving, and an acknowledgment of its function as the ultimate manifestation of our most essential dreams.

After a long struggle, the Austrian Cultural Center on East 52nd Street, which Abraham designed, is now nearing completion. The facade of this 20 foot-wide, 23-story building appears to hover above us, as it establishes a limit between the interior and architectural elements that protrude into the public space. It is a unique and singular testament to the art of building.

Carlos Brillembourg: Raimund, tell me about your idea of tension between the ideal and the built as an essential condition for architecture.

Raimund Abraham Anybody who makes architecture has to recognize that phenomenon: it is the ultimate challenge. But one really has to define the context. Because this tension between the ideal and the built remains in the context of building—it’s not taking place in the context of drawing. In the context of drawing, it’s a completely different dialectic. When I draw, the drawing is not a step toward the built but an autonomous reality that I try to anticipate. It’s a whole process of anticipation, anticipating that a line becomes an edge, that a plane becomes a wall; the texture of the graphite becomes the texture of the built. Now, when you translate the drawings, one also has to distinguish between the drawings you make in this autonomous process—where the drawing is the ultimate reality. I draw first for myself, not for somebody who is building—which means there has to be an absolute clarity in my mind, and the ability to retain the idea that I’ve established in the drawing, and furthermore, the anticipation that this idea will be buildable. Of course, it’s a highly complex process, and I’m talking about the first stage, which is a dialectical confrontation—of whether what I draw will be built. From the moment I know that something is going to be built, my drawings become something else. And at that point I draw less and build models immediately. One really has to distinguish between those different phases.

CB It’s a question of approximations through layers and also through different goals.

RA Yes. One has to reinvent, and in that sense, define what that ideal truly represents. Geometry, I would say, is the language of the ideal. And, of course, one knows precisely that what could be complete as a geometrical configuration could, in a way, not be built. So there is a transgression of ideal configuration—geometry—that has to be confronted with the buildable. When I say buildable, today you can build anything, in terms of technology. I mean buildable in that materiality would be transformed by the ideal of geometry.

CB You are talking about a convergence of the ideal as translated through the geometry into the material.

RA Absolutely. A wonderful example is the Pueblo Ribera Court that Schindler did in La Jolla—very modest, small atrium housing with wood construction. It has more or less deteriorated physically over the decades. And it’s overgrown. Yet you can still read, through the profusion of ivy, the ideal lines that had first been drawn. You see, that’s what I am really talking about with the buildable. That the geometry is more or less transgressing materiality, no?

CB So therefore the ideal reemerges.

RA Sure, but it has to be felt in its original intent. You see, that’s another phenomenon that I think we have to discuss. If geometry is not confronted with materiality, it remains infinitely manipulatable. For example, if you take present-day fashion in architecture, you can see that there’s no challenge to the limits of that geometric configuration. To modify Gertrude Stein’s “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose,” you can say circle is a circle is a circle, square is a square is a square—until a material challenges it. A square in concrete, a square in steel, a square in stone, is a different square. Because the ideal line is challenged by the nature of the material. Each material has its own limits, its own potential, its own emotional power. So these two worlds are actually not reconcilable. It’s neither form follows function nor function follows form. Form and function have to be confronted. And that is the power of architecture, or, I would say, the possibility that you deny function in architecture. See, I can say I deny light, illumination, I deny vision. The denial is a confrontation. The moment you recognize that utility and form are irreconcilable entities, you have architecture.

CB You seem to be saying there is a kind of tectonic reality, which is within the material.

RA Yes.

CB Which implies almost an ideal geometry in itself. And there’s a confrontation between that tectonic reality of the material and the latency of its idealized form.

RA It’s a critical dialogue, which can be clearly applied to the computer issue, which is now a hot topic. How is the computer influencing architectural thought? From the moment you design with the computer, it is mind to mind. And there’s never a confrontation with matter. So if the primary ideal is the thought, then the next is the ideal of each discipline you utilize to manifest that thought, which is the architectural drawing, no? The next step is the model. And then the use of the computer as a survey device to help overcome geometric complexities that would be harder for the hand to draw. The computer cannot substitute for this process. But at least when I do a drawing or model and then use the computer, the computer is already confronted with matter. Anticipated matter.

CB Some say the computer is now able to manufacture specific pieces of architectural material in a handcrafted fashion on a mass-produced basis.

RA It’s the same argument about any sophisticated machine that has assisted in the evolution of efficient production. If you look at Diderot’s Pictorial Encyclopedia of Trade and Industry, which deals with manufacturing from mining to architecture, you find a knowledge of geometry and an anticipation of spatial conditions that have been lost. They are complex beyond what the computer could produce. The computer assists you in simplifying that process. It’s different if you have to construct that curve, because then you have intimate knowledge of the translatability of that curve. If you go to Bilbao to see Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim, and really look, after you’ve overcome the spectacular moment of the first visual encounter, and examine the details, spatial or structural, you discover that it has been built in order to satisfy shapes. It has not been designed to respect the confrontation between mind and matter. It simply is buildable. You see steel trusses running into Sheetrock walls and they will be there wherever they are needed. And that of course is when the computer is extremely helpful, because it more or less satisfies its own mind. Yet this mind is still extremely rudimentary. Coming back to the origins of your question, it is that confrontation between the ideal and matter that has to take place, or the process is meaningless. I say meaningless because you don’t really know what the limits of the line are. If you have never lifted a stone, or a brick, or a bag of cement, you have no clue what concrete, bricks, or stones are, no clue.

CB Does it ever happen that you finish a building—it’s built—and you keep drawing it?

RA No, never. I only make drawings that are necessary for satisfying a vision I have that is manifested in the drawing, or a drawing I need in order to build something. I met Aldo Rossi in the early ‘70s and he worked exactly the same way. It was why we began an immediate friendship—we shared the same convictions of making only what is necessary.

CB Aldo once said something very beautiful to me—which was very central to him. He said he actually never stopped drawing a project, even after it was built, because the building of it was just one phase in his understanding of the project.

RA For me, when I finish a project, I forget it. If you asked me to draw a plan of a house that was built 10 years ago, I couldn’t do it. Because I’ve lost interest, there’s no intensity. Also, I’m very bad at drawing something that exists. I’m never really tempted, when I go to see a fantastic site, to sketch it. I’m only interested in sketching to work out what does not exist. The moment I finish a project, it belongs to history, manifested in its own memory.

CB Your architecture recognizes a state of decay or erosion. Would you say that the erosion of the material to its most essential form uncovers a timeless, more essential architecture?

RA I would have loved to do that, to have erosion manifest itself. Can you be more specific and give an example?

CB In your drawings, your architecture is implanted within a landscape. And the forces of that natural landscape, the erosion and the plane of the sky against the horizon are carried literally into the architecture.

RA I would not call it erosion, but rather the anticipation of decay. Meaning that this is the fate of architecture. The ancients anticipated decay. Take the Acropolis, or the Parthenon, which has been destroyed twice and still is complete. Coming back to the first question—the ideal of that structure is built into every line. That’s why you can also reconstruct the Great Temple from only a few fragments.

CB So the ideal is in the fragments?

RA Each detail reflects the total integrity of the building.

Raimund Abraham, Austrian Cultural Center Construction (side view).

CB I couldn’t agree more. The question about erosion came up because it seems evident in the drawings, which I understand now to be, in a way, not built projects, but projects of translation from an ideal into the physical form of the drawing.

RA I’d like to make a clear distinction among what I call imaginary projects, projects, and buildings. Imaginary projects are autonomous manifestations of architecture. Whereas projects are how I invent the site, the habitation of the program, and all the conditions, which then become ideal images that I then have to confront. Now in projects, I’m dealing with sites that have their own past, their own limits, their own possibilities. If I take any competition project or any project in which I chose to participate in cities like Venice, Berlin or Paris, it is there where I’ve had to confront my ideal with preexisting conditions rooted in their own memory.

CB Or the ontological site…

RA In my imaginary work, I always think one to one, not in scale; the scale is simply a device to measure things. So, in the projects, I try to retain the ideal in respecting the limits of the site. Before I even think about constructing a building I have to fully comprehend the nature of the site, and those forces which determine the nature of that site, its historical past, its potential future. It’s those forces that stimulate me, inspire me, and ultimately define my ideas.

CB In your writings you often speak about the ontological basis for architecture as originating from the disturbance of the archetypal site of the horizon. Is this the fundamental act of architecture, the destruction of this site?

RA The fatal nature of architecture is that it interferes with an equilibrium ideally or physically. It’s what I call the ontological site, which reduces a landscape simply to the horizon, the collision between sky and earth. A more complex intervention can only be realized by understanding that fundamental way you either violate the sky or the earth. You have to understand the fragility of the world we live in. You can apply this same thing to cooking. When you slaughter animals, or you cut down plants, the only way to respect that violent act is to cook well. Cooking, not as a process of satisfying hunger, but a way of showing respect for what you have, and what you have killed.

CB Can you talk about the Austrian Cultural Center in terms of this dialectic of destruction/creation-and of the sky plane and the ground plane within an urban context?

RA Within the context of this particular site, the dialectical condition is manifested by the lateral compression of the void, defined by the weight and height of the neighboring buildings, and the geometrical definition of the zoning envelope, as defined by the building code. The tower rising autonomously between the existing walls of the adjacent structures is defined by three syntactic elements, the VertebraStair Tower, the Core-Structural Tower, the Mask-Glass Tower, signifying the counterforces of gravity: Ascension, Support and Suspension. Both the stair-tower as well as the curtain-wall strive for infinity: the stair-tower vertically, the curtain-wall diagonally. While the stair-tower is rising, the curtain-wall is falling by suspended sheets of glass and metal. There were two decisive issues for me in defining the material and geometric articulation of the curtain-wall. I have never been intrigued by the illusionary transparency of glass, but rather, like Mies van der Rohe, by its mineralogical origins: heavy and precise. To achieve the knifelike cutting edge of its planes, all outer metal frames are mitered toward an infinitely small line. The angle of its ascending planes is derived from the angle of its zoning envelope. The tower itself can be defined as an interstice between the stair-tower and the curtain-wall.

CB So, it is important for you to communicate this idea of suspended gravity on the facade.

RA Yes, but this is in all my projects. I never really know how an idea comes into being; there are many, many factors. When I look at my own completed work, I become as speculative as you or any other critic. I only eliminate speculation while I’m working. When a building is completed I become a spectator, because it doesn’t belong to me anymore.

CB Looking at your drawings and your built work, there is a recurring theme of symmetry—the central axis is expressed physically as an obstacle, and sometimes as a kind of incision—more specifically there seems to be a bilateral symmetry. What does symmetry mean to you?

RA For me symmetry has never been an aesthetic device but rather an ontological perimeter in the dialectical conflict of stability and instability. Depending on particular conditions of the site, the recognition of particular vectors, their impact on space and time shall articulate the dominance of special geometric strategies. It seems that the fear of symmetry in our time and in particular the association with its politicized abuse in history has led to an architecture ideology of asymmetry and consequently to a game of spectacular, but meaningless formal manipulations. In my work symmetry is always challenged, sometimes subtly, sometimes radically, but always in plans and sections, sometimes hidden within the interiority of space.

The tower of the Austrian Cultural Institute, a vertical slice 25 feet wide and 280 feet tall, became a deliberate manifestation of utmost formal reduction, challenging the indigenous variations of the surrounding buildings while the symmetrical spinal structure of its mask reflects necessity, not choice.

CB So for you symmetry can be fearful or oppressive, or it can be an organizational tool.

RA I would not grant it the power of fear but rather the power of oppression we recognize in many manifestations of architecture in oppressive political systems. But since the perception of architecture is contemplative and its focus is less demanding than the perception of literature, cinema or music, its oppressive power, its use for political propaganda is weakened and becomes less effective.

CB So architecture is ineffective propaganda.

RA You can walk down a street and ignore its details. You get a mood that can be either stimulating, inspiring or depressing, but to focus on the structures around you, you’d have to use a completely different strategy of perception. I remember Venice as a child, I was overcome by its beauty. The first time I lived there, it was a few months before I started to look at details. How bridges were built, how stones were connected—and all of a sudden I had a completely different insight. The city became another reality.

CB What you are saying is that architecture is ultimately successful only in raising your spirits through attention, through close observation of the architecture itself. Because if it is depressing, you are not going to look at it.

RA Ultimately, the aspiration of an architect is to make something sacred. There has always been a confrontation between the profane and the sacred. Successful architecture carries some degree of sacredness—otherwise it is not architecture.

CB That is a very strong statement.

RA That is really what it is.

Raimund Abraham, Surveyor’s Tower, 1997, sketch.

CB What role does technology play in the confrontation between the ideal and the built?

RA Technology can be either an inspiration and tool, or it becomes a domain where you more or less yield your possibilities. As an inspiration and tool, it is not necessarily evolutionary, although weak artists of all disciplines are always jumping onto new technology in order to be avant-garde. For example, after cinema there was video; video appeared to be a much more advanced device. I am not denying that video has its own recognizable validity, but cinema is a completely different discipline. Video didn’t replace film, it wasn’t more advanced. In the same way, to claim that digital reproductions are more advanced than painting would be silly. And architecture is exactly the same. I am building a little house for myself in Mexico, in a very remote place, and I had to recognize the limits of the available technology, which are adobe brick and wood, and I still succeeded in making a house that is very different from anything that has been built there. It is a question of translatability, what you can do with theory. You have to understand material, you have to have a dialogue with it, you have to ask questions about what it can do, what it can’t do, which doesn’t limit you at all in your formal vision. It’s fascinating to me that the bricks I used have the same color as the earth I dug into on my site. I exposed a lower layer of earth the same exact color as the brick. It was hidden down there, almost like when you puncture your skin and a drop of blood appears.

CB In your book, Elementare Architektur, you make a point about the architecture having developed in relationship to the land and the materials coming from that land. So the question of nature and architecture is a relationship that is always present.

RA It’s there but you have to recognize it. I grew up in the Alps, so I made Elementare Architektur exactly at the transition from finishing my studies and really starting to think about architecture. I felt that I had to take my memory of the Alps and manifest it in an abstract way, recognizing the power of structures. Interestingly, I only chose structures that either store hay or house animals. Those structures don’t yield to the taste of their inhabitants-which informs certain residential elements of that indigenous architecture, so there is a structural sacrifice. In elemental structures there was no necessity of aesthetic speculation—it was more or less the knowledge of the builder that determined design. Of course, it is not only the yielding to that knowledge—the builders also had formal ideas, such as a whole series of different door handles carved out of wood. Where is that coming from? It’s not the necessity of the wood, it’s the desire of the builder.

CB So there is a kind of creativity within this vernacular.

RA Within limits, yes.

CB So the question of technology and architecture has more to do with the nature of the materials rather than the substitution of one technology by a more advanced one.

RA It goes without saying, any technology offers different ideas.

CB We have to question the idea of history and advancement. Where are we going when we go forward?

RA I don’t believe that there is any advancement of thought. None whatsoever. There are different responses to the world, at different times. Furthermore, there is no manifestation of a new possibility totally independent from anything that happened before or after.

CB The Mayans use a circular calendar.

RA That’s fascinating, because it reflects a different reading of the cosmos. That it’s considered less advanced than our linear calendar is ridiculous. There was this struggle in America in the ‘60s where for economic reasons (naturally) they wanted to replace the U.S. measurement system with metrics. All of a sudden people fought to retain the old system because they realized it was cultural (baseball is not sport, it is culture). In each system there is a cultural consequence, cultural origins.

CB You often speak about Modernism as expressing a radical break with historical continuity. What exactly does that mean, if there is no diachronic history?

RA You see, until then, historical developments were described in terms of formal differences. Even within the Renaissance you had drastically different architecture, by Alberti and Palladio, yet it’s all thrown into the bag of Renaissance architecture.

CB Actually, Palladio was more of a Mannerist architect than Renaissance.

RA I have to recapture the question.

CB It’s about a radical break.

RA Right. Modernism, for me, was the first time that not only the past was challenged, but the language of each discipline was challenged. Going back to my description earlier about the horizon as an ontological site, try to reduce the whole world to a line where two dimensions collide. That was the intent—Malevich’s attempt to paint the white square on the white canvas, Mallarmé’s obsession with the whiteness of a blank page, you have Mies van der Rohe’s unbuilt corner. They are all attempts at reducing language to its true zero, its condition, its origins. And that is ultimately what originality means, the ability to dig down, to cut. In terms of my own confrontation with history, I always try to cut through it. I interchange historical events, a pyramid in Mexico with a Melnikov project…

CB You’re talking about the collapse of time.

RA Absolutely; time becomes infinite when one succeeds at making a project that is not bound by time.

CB And that is your goal.

RA That is the desire. I know there is truth, and I desire to find it.

CB Can you speak to us about your role as an educator, somebody who has dedicated a great deal of his life to educating a number of architects?

RA Teaching forces me to engage in a critical dialogue with somebody else, and find a level of objectivity that allows me to have a fair critical argument. My role as a teacher is simply to clarify, although that’s a bit simplistic. When I give a problem to the students, it’s my problem, I am trying to anticipate how I could solve that problem. And my joy is when the students come up with a solution I haven’t thought of. And in that process, I can help to clarify their intent. If a student has not established an idea, I do not teach. I don’t give ideas. So I wouldn’t call this being an educator, I am perhaps a provocateur. (laughter)

CB It’s the Socratic method, education as dialogue.

RA I don’t believe in education. When I think back to my days as a student, I didn’t learn anything from professors. We formed a group of students who engaged in critical dialogues and almost ignored the faculty. As a teacher, I have a loyalty to the freedom of engaging in architecture, and there cannot be an ideological preference, an aesthetic preference by the faculty to exorcise that freedom.

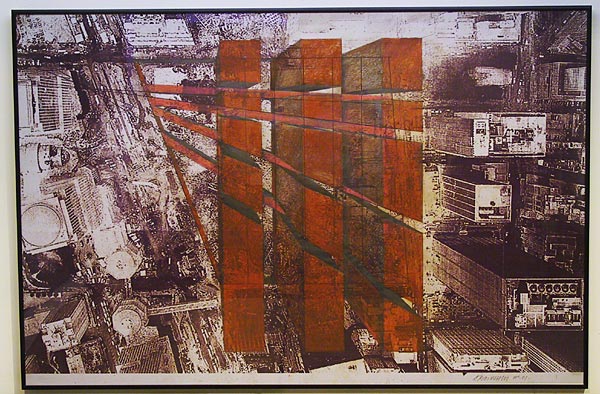

Raimund Abraham, Times Square Tower, 1984, photo montage.

CB I am interested in discussing the relationships among painting, sculpture and architecture.

RA Each discipline has its own narrative, which has to be challenged by the syntax of its language. One could identify the narrative in architecture as use—none of the other arts have to be used. So in architecture, contrary to the limits of sculpture, any formal decision has to be confronted with utilitarian issues. If architecture succeeds in retaining its universal ideal, it will still reflect its confrontation with use. I can deny access, but in the denial one has to measure the confrontation that took place. I can make a room that is not accessible, for example, but it cannot be an accident, it has to be a conscious intellectual discourse with the project; that is the narrative in architecture.

CB There is a kind of contemporary confusion about the limits of sculpture and the limits of architecture.

RA Any discipline seems to somehow overlap by affinities. The earthwork definitely has architectural origins, but does not have to yield to the confrontation I just mentioned. So in that case the sculptor has an advantage in a way; the work can remain abstract without going through that painful process.

CB Were you influenced by Robert Smithson in the ‘70s, or other artists like him?

RA I am never aware of a specific influence—there are so many influences. I believe that architecture relates much more closely to other structural languages like cinema. I was very influenced by cinema, literature, music. These are the three disciplines that are most closely related syntactically to architecture, more so than painting and sculpture. This is where the confusion comes from regarding architecture as the top of the so-called visual arts. Architecture is not a visual art, architecture is a structural art. In music, if you shift one note in a classical score, one line to another line, it is another sound. It’s been said that the essence of architecture is the understanding of how one stone sits on top of the other. It is the seam between the stones that defines intelligence or precision.

CB You had a deep friendship with Frederick Kieslei an artist and architect.

RA That was an unforgettable experience. The last year of his life, when I visited him, I entered his studio and heard a faint voice from somewhere, so I followed the voice. He was working on a sculpture of a horse lying on its back with its legs stretched into the air. He was lying inside the belly of the horse and writing a poem in gold letters on the inner shell of the horse’s body. And I realized immediately that there was such an incredible spatial affinity between the belly of the horse and his endless house and his obsession to discover a new space different from all space he had ever known; a total metamorphosis of a single idea removed from its content.

CB Your work always incorporates the presence of nature. In the drawings, there is the sensation of an architectural object presented within a natural field that is abstracted. Does this relate to your idea of the ontological origin of architecture, as this constant meeting of the sky plane with the ground’s plane?

RA This came much later when I intellectualized my relationship to nature. Now my interpretation of nature is really rooted in my childhood. Growing up in the mountains, out in the country, I was always fully aware that one must confront nature and not deceive it. The farmer takes the plow and cuts it into the earth before he sows the seeds. Actually, in terms of architecture, my ability to measure precision really comes from mountain climbing, where your life depends on it. You have to read a wall of rock if you want to climb it; you have to understand its geology, and know, when you hold onto a piece of rock, that it’s solid. And when you ski, when you race, you have to understand the crystal condition of the snow. The snow is not a white Christmas—it is a medium, a material you have to work with. Now, in my practice, I can intellectualize what was originally a pure experience. Take the measure of time, for example. I would say that time is physical. When I go back to my hometown and look at the mountains I climbed (which I cannot climb anymore), I know how long it took to climb them. So by looking at the landscape I have a complete measure of space and time. And that is very important in reflecting upon architecture. Architecture cannot be an image, architecture is a construct.

CB So there is nothing picturesque about your view of nature.

RA Exactly. Incorporating nature in my projects is an obsession. I believe that anything you build is primary intervention in a landscape. Even if you look at an urban site—you can say that’s a lot, or a void between buildings, yet you know that there is rock down below and sky up above.

CB When I look at your drawings, or pictures of your architecture, I conceive of architecture as a kind of verb. I see the walls, the entrance and the spaces interacting directly with the mind and the body and the materials of which they’re made.

RA Meaning the work is an action. It is that act of being aware that the primary force is an event, an event in which you intervene. First you dig a hole or make a mount and then you decide if the mount is a pyramid, a cone, or a cube. Or you come upon a hole in the ground that is six feet long, two feet wide and five feet deep, and you know that that’s a tomb, a grave to receive the body and turn it into earth again. That is the origin of architecture.

CB In your work you have insisted upon the program of the house as a kind of universal typology, this business of habitation as something that limits the original condition of architecture.

RA Well, habitation for me is about ritual. In terms of interpreting the program for a house, if you think in terms of bedrooms and bathrooms and living rooms and garages, then you are already doomed. We have to talk about sleeping, about eating, about cooking, no? Living room, I never understood what that meant, because you live everywhere. I really believe that there can’t be a new architecture if there aren’t new interpretations of archaic concepts. So coming back to your verb, I like that idea, because the verb is frozen on a piece of paper yet it’s kinetic, force is ever present.

CB How does one reconcile the confrontation of the original condition of architecture against the accumulated condition of habitation as seen through urban structures?

RA Urban structures for me are simply a man-made landscape, but to approach the city like you approach a landscape would really be a mistake. The city is a result of a highly complex program that can never be truly defined and categorized. Take so-called housing; housing is a weakening of the house. For whom is this housing? I don’t know those people who are going to inhabit it. Now, one could maybe ignore this whole social complexity in the city, and start to identify only its typology, rather than try to interpret and verify the condition, and build according to it. The ‘20s and ‘30s in Europe were a manifestation of a compassion for social change—there was a house for the worker, a workplace for the worker, and the church. They tried to make sacred places for the worker and sacred places for the worker to work in. There was a respect for human programs. And I think what’s been really detrimental to the understanding of the city in our time is a master plan mentality—which is still evident in the so-called urban typology. The mapping of the city is essentially like trying to extract some kind of artificial intelligence out of a highly complex organism. Which is a total misunderstanding of the city. In New York, for example, if you walk from all the way uptown to all the way downtown all of a sudden you realize that there are invisible thresholds—you cross over by one street and you are in a different world. So how can you ever speculate what will come into being? I believe if you build one thing, and this one thing is defined by clarity, compassion, and belief in the true survival of the city, then this singular building will become a singular force within the unpredictable metamorphosis of the city: “The house is the city—The city is the house.” (Alberti)

Raimund Abraham in

Raimund Abraham in  Interview,

Interview,  Transcript

Transcript Raimund Abraham's Last Lecture

Friday, June 4, 2010 at 9:46PM

Friday, June 4, 2010 at 9:46PM Watch it here

http://www.sciarc.edu/lectures.php?id=1657

Raimund Abraham in

Raimund Abraham in  Lecture,

Lecture,  Long,

Long,  Video

Video